Corals

Mushroom Coral

The genus name is Fungia - a good name for a Mushroom Coral. These are one of the few corals that live as solitary large polyps and do not become colonies as most corals do. Because they are large (up to 20cm across) looking at them is a great way to learn about corals. They have the mouth in the centre - you can see it here - with the septa (structural walls of the coral) radiating outwards. Like all corals it has symbiotic zooxanthellae in its tissues as well as tentacles that catch passing prey such as plankton (mainly by night). As juveniles they are attached to the substrate (the reef surface) by a little stalk just like a mushroom. As the coral grows, the stalk falls off and the weight of the coral keeps it on the bottom.

Galaxea - a galaxy of stars

Tiny but very beautiful, this coral forms small rounded or encrusting colonies with often flurorescent green tentacles that are frequently open and feeding during the day. The high and pointed septa give the corallites a star-like appearance.

A closeup of a large polyp....

Probably Lobophyllia, you can see the tissue covering the skeleton of the coral quite clearly. Each corallite (the cup containing each polyp) is about 3-4cm across, and the colony as a whole can grow up to 1m or so across.

Soft corals.....

While they don't have a hard internal skeleton, the soft corals are an important part of reef life - providing habitat and food for many reef animals. The tentacles on soft corals are usually fringed, and in groups of 8 (hence the name of their subclass is Octocorals), whereas hard corals have simple tentacles on the polyps and are in groups of 6 (hence their name is Hexacorals).

Honeycomb corals

Forming round colonies of various sizes, the corallites look like round honeycomb shaped dents, the mouth in the centre. Again the tentacles come out at night to feed, with daytime being when zooxanthellae (the microscopic plants) produce nutrition as proteins and carbohydrates for the coral. Honeycomb corals are identified to species by the way the corallites join onto each other - forming ridges or valleys and the way the septa are laid out. This one is probably Favia rotundata.

Why is the top of a reef flat?

Reefs don't grow into mountains or hills. Why? Corals are living animals as we know, and they dry out if they are exposed to the air for too long. So how long is too long? While corals produce a remarkable mucous that lubricates them and has a high level of coral "sunscreen" this mechanism can only work for a short period. Low spring tides expose the top of the reef for a few hours just a few days a year. Growth that has occurred over the past year may be killed off with this extended exposure to air and sun. Sometimes we see the top of a reef appearing white as snow a few days after the low spring tide - especially if it has been a bright sunny and hot day.

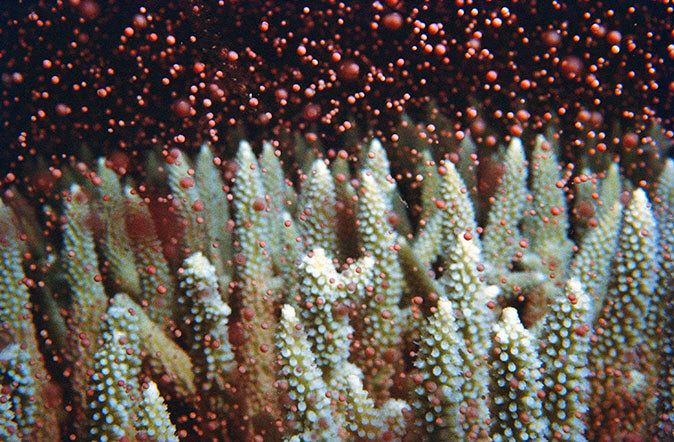

Coral Spawning - an annual event

Corals expand their colony by reproducing asexually and budding off more polyps along their branches for example. But each year, they produce eggs and sperm for a single night of a coral sexual explosion when these gametes mix like a pink soup in the water. Indeed, it is a fabulous soup for predators such as fish - which is why the spawning is at night when fish sleep and is synchronous within a coral species on a particular reef so that there is a good chance of fertilisation in the vast ocean. Any predators that are around for it (such as night feeding plankton and fish) have a complete feast but can only eat a limited amount in one go - maximising survival for the corals. The fertilised egg becomes a planktonic larva until it becomes heavy and settles on a reef to become a new coral where it asexually reproduces to form a colony.